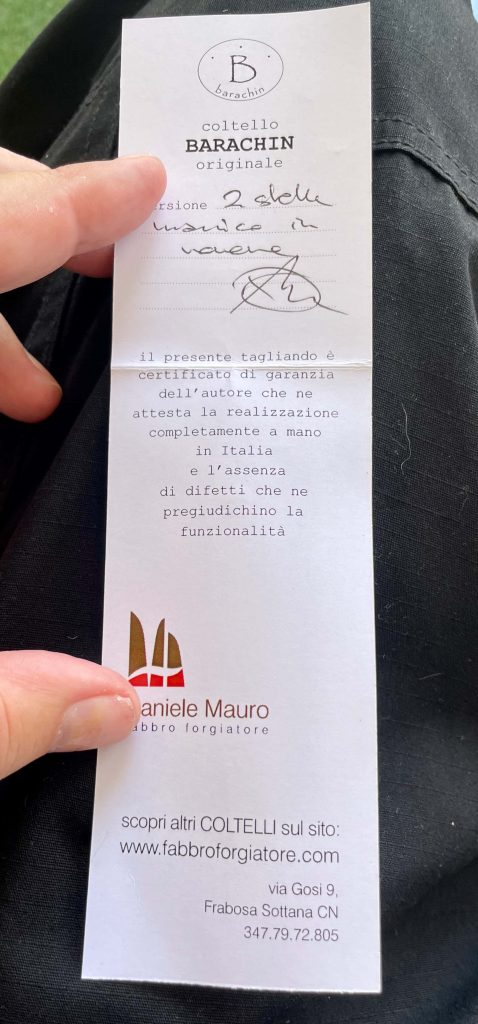

A Piedmontese barachin knife

*The barachin knife is the best-known craft knife of Italy’s Piedmont region (the other knife of local fame being the “Piemontese” pocketknife). After admiring the barachin for 15 years, I finally bought one of my own.

*Why? I already own other knives that are much better than a barachin. The barachin is a farm tool. It’s a small, lightweight pocketknife with a thumb-latch and a modest wooden handle, best suited to light pruning in vineyards, orchards and gardens.

*Of course any modern Piedmontese farmer would be much better off with some modern multitool. Contemporary European Union farms are complex enterprises, technologized, subsidized and regulated, so that a barachin is too rude and simple to be practical for modern agro-business people.

*A centuries-old barachin might be an interesting antique. However, these humble knives were never intended to last for centuries. I’ve seen some “modernized” barachins, with high-performance steel blades and carbon-fiber handles. I was not much tempted by those; they strike me as perverse. They’re not rustic — they have the barachin’s shape without its traits.

*So I bought a modern barachin — which is an outmoded farm tool that will sit near a writer’s desk and very likely never see a day of farmwork. I opened a some packages with it, just to see how it functions as a cutting tool. It’s fun to use, very light-weight, deft, modest, almost an art-knife. You can’t gut fish, or skin and butcher farm animals with a barachin, and it’s so small and modest that to do serious vineyard pruning you’d likely be better off with a sickle. But its ergonomics are quite good — when you steady the blade in the grooved handle, by pressing the thumb-latch, you have firm manual control of a small, deft slicing tool. The blade has a sharp stabbing point, but it’s certainly not a menacing and aggressive knife; more of a potato peeler.

*The barachin’s modest little blade looks hand-forged (because it is) and its handle is hand-carved, hand-smoothed Italian wood. The wooden handle is unadorned, and the steel, although sharp, is brittle. If my knife was ever used on some real farm, it would soon be nicked, rusty, sweatstained and dirt-stained, because such is the natural, and even the satisfying, state of farm tools.

*So, for me, a barachin is a conversation piece. I have a barachin because I can blog about it. Maybe I will show it to a classroom at design school some day. The truth is, though, that I am a long-time student of Italian craft traditions — I spend a lot of time reading and thinking about them. It would be a shame to lack personal, hands-on familiarity with this particularly famous example of Piedmontese invention.

*Also — rather than obtaining some old museum-piece — I consider it important to encourage today’s museum economy and its contemporary products. I own a replica barachin made for collectors, but I think it’s better, and it’s even wiser, to maintain the cultural career of the barachin, in Piemonte, than it is to preserve and extend the unnatural life of some particular historical barachin. The original barachin was a modest, practical, workable hand-tool that a farmer-blacksmith could likely pound out and pop together in a couple of days. They were abandoned without remorse whenever the rust and dirt and hard use did them in. No one ever built them for museums.

*This new, yet oddly antiquated barachin that I just bought was not cheap, but I’m not merely buying iron and wood. Instead, I’m deliberately playing patron to a long-lasting regional tradition, and I’m glad I did this. If I ever lose this particular barachin, or if I give it away as some gift of esteem, I’ll likely promptly buy another one.

*In the meantime I’ll continue to carry a Swiss Army knife in the city of Turin, because I always have one handy and they make much more sense for me.